Cathy Xiong, Teen Advisory Group

Abstract

Asian-Canadians are underutilizing mental health services despite experiencing equal, if not higher, amounts of mental health concerns. In this study, the identified demographic is newly immigrated East-Asian youths ages 15-17 due to their vulnerability to mental health concerns and low percentages of seeking help. This discrepancy in health care usage stems from stigma concerning mental health illnesses in the East-Asian culture, lack of English proficiency causing language barriers and a lack of cultural understanding within mainstream mental health facilities. It’s known that mental health campaigns are effective; however, for certain demographics than others. Therefore, the goal of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a culturally-focused mental health campaign in effort to mitigate these three cultural barriers for our targeted demographic. This study uses the Mental Health Attitudes Seeking Scale before and after a mental health campaign developed based on these identified cultural needs. It was observed that respondents had more positive attitudes towards seeking mental health assistance and were more likely to seek different types of treatment post treatment. The implications of more East-Asian youths seeking mental health help earlier with the right kind of treatment decreases the resources needed for untreated mental illnesses and can increase representation of this community within the mental health care system leading to the development of more effective treatments.

Introduction

Asian Canadian Mental Health

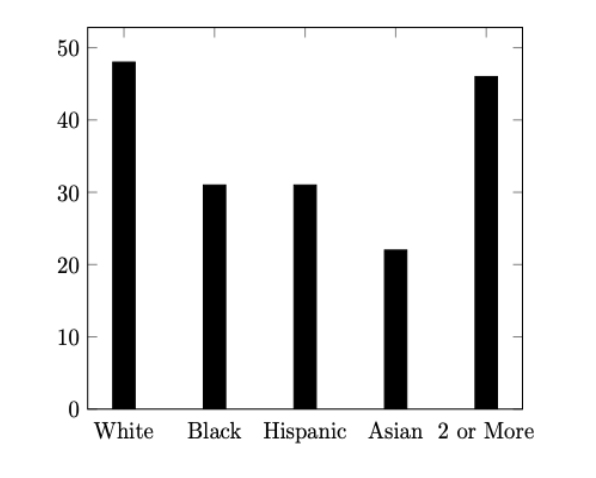

Despite a total of 6 million people with Asian origins in Canada, and around 50% of all incoming immigrants from Asia, there still exists a limited cultural understanding of this minority by mental healthcare providers (Statistics Canada, 2021). Stigma surrounding mental illnesses in Asian traditions, lack of available lexical and language, and Asian patients’ experiences in mainstream healthcare may impel potential patients in avoiding mental health care. To better understand this complex issue we must acknowledge the presence of the Model Minority Image. This image characterizes Asians as “resilient and healthy” in accompaniment with hardworking, and disciplined mannerisms—traits that aren’t often linked with mental concerns (Speller, 2005). Consequently, this perpetuates the notion that Asians may not have mental health concerns due to their resilience. In reality, Asian Canadians do “experience mental illness and have an equally high, if not higher, need for appropriate mental health services as any other racial or ethnic group” (Speller, 2005). In a study of around 800 Asian Canadians in Toronto, it was documented that “the percentage of people who have mental health difficulties [were] as high as that of their Caucasian counterparts” (Fairfax, 2017). This raises concern as Asian Canadians are underutilizing mental health care, with only 4% willing to seek “help from a psychiatrist or specialist” compared to 26% in caucasian communities (Center for Mental Health Services, 2001). The relationship in the following figure demonstrates the discrepancies throughout ethnicities and mental health service access.

Figure 1: Percent of People with Mental Health Issues Receiving Services in 2015 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015)

This begs the question: If the Asian Canadians community is experiencing such a high percentage of mental health concerns, why are they unwilling to seek help?

Literature Review

East-Asian Immigrant youths

This study’s targeted demographic will be East-Asian Canadian immigrant youths due to their vulnerability to magnified environmental stressors as well as their influence by the dominant religion of Mahayana Buddhism. In this study East-Asian youths include youths with origins from China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. To begin, Asian adolescents (ages 15-18) are experiencing high levels of anxiety and are reaching “the clinical threshold (for stress) more frequently” (Xia, 2021). This could stem from parental stressors and the Model minority image, whether within an academic or social setting. While this may be countered with the belief that all youths are experiencing stress and everything is situational, the severity of stress experienced by Asian youths is intensified during immigration—a process notall youths will face. Immigrants who have experienced the act of moving are considered to be at a high risk of mental health concerns since the transitional phase of moving to an unfamiliar culture can “magnified stressors” (Speller, 2005; Cader, 2017). As a result, additional stress can exacerbate previous mental health concerns, which for Asian youths, that are already at an all time high. The extreme levels of stress experienced by these youths can often evolve into other mental health concerns (Xia, 2021).

Surprisingly, there is a discrepancy between East and South Asian and their mental health: “East Asian boys are facing higher mental distress, at 22 per cent, compared to south Asian boys, at 11 per cent” (Xia, 2021). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that East-Asia and South-Asia have different dominant religions. In East-Asia the dominant religion is Mahayana Buddhism, while in South-Asia their dominant religion is Hinduism. Between the two, there are differences in attitudes concerning mental health. For example, in Buddhist culture, the mind and the body are not separate, thus mental health concerns are only an extension of physical problems. However, in Hinduism, while there exists stigma concerning mental illnesses, there exists the belief that the “evil eye” concept or karma may be the cause of mental illnesses. While Buddhism tends to shy away from the direct acknowledgement of mental health illnesses stemming from cognitive dysfunction, Hinduism acknowledges its the existence of mental illnesses. The denial of mental health concerns within Buddist countries may have placed East-Asian youths to be increasingly vulnerable to mental health concerns. Therefore, justifying the necessity to base this study around young East-Asian immigrants.

Cultural Barriers

Stigma

The most prevalent and extensive barrier impeding access of mental health services for East-Asian Canadians is the stigma associated with mental health concerns. To begin, the confucian culture found in East-Asian communities emphasizes harmony and resilience, leading many people to believe that “coping with depression” is “more beneficial than seeking assistance” (Yang et al., 2019). This notion propagates the beliefs that seeking mental health treatment could be a sign of weakness rather than taking responsibility for one’s health—which highly contrasts Western thinking. Moreover, a study in Singapore, a multi-racial country constituting more than 70% East-Asian residents, corroborates the stigma presented in East-Asian culture (Encyclopædia Britannia, 2021). A nation-wide survey was given to note attitudes towards mental health. Around 40% of the respondents believed that mental health problems are dangerous, and half believed that the public should be “protected from them” (Chong et al., 2007). As a result, many will hide their mental health concerns within the family in order to avoid shame and dishonor. In addition, as symptoms progress, many will seek treatment such as “traditional herbs and acupuncture,” “healers,” while others will simply refuse to acknowledge the illness rather than seek mainstream treatment (Kramer et al., 2002). These treatments may include psychotherapy, counseling, prescription, support groups and brain stimulation therapy. Due to this high level of stigma, professional mental health services are only considered as a last resort.

Language

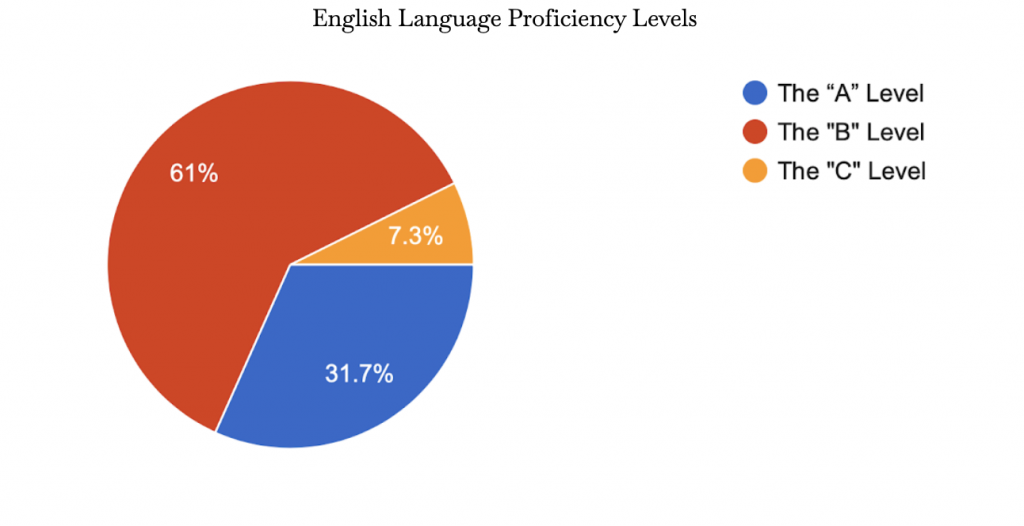

Often, East-Asian immigrants may encounter language barriers as the majority of mental health services are only offered in English in Canada. For example, only 42% of foreign born Asians are considered English proficient (Pew Research Center, 2017). One can assume that these individuals have the capacity to explain their mental health symptoms in English. Another factor to consider is that these foreign borns may have immigrated at an early age, thus may not have grown up in a traditional Asian household due to acculturation . In addition, most likely these Asian foreign borns didn’t have to make the cultural transition from immigration during adolescence (Xia, 2021). Therefore, the English proficient population can be considered to be at a lower risk for mental health issues comparatively to new East-Asian immigrants. Nevertheless, the question arises; what makes the other 60% who aren’t English proficient? They will face difficulties in accessing mental health treatment as they will not be able to describe their symptoms to receive proper diagnosis (Cader, 2017; Kramer et al., 2002).

Despite there being options for an interpreter, patients often “feel uncomfortable and hesitant to disclose their problems” in front of strangers in fear of losing ‘face’ and honor (Speller, 2005). Therefore, limited English proficiency (LEP) among East-Asian patients is an issue. A study published in the US National Library of Medicine claims the following:

Compared to [English proficient] EP individuals, LEP individuals with mental disorders were significantly less likely to identify a need for mental health services, experience longer duration of untreated disorders, and use fewer healthcare services for mental disorders, particularly specialty mental health care. (Bauer et al., 2010)

Patients will avoid and delay treatment due to language barriers, thus providing services in their first language would be beneficial in decreasing discrepancies in mental health accessibility.

Moreover, even when a patient is willing to seek help, there is a “lack of descriptive psychological vocabulary” that can describe mental health concerns in East-Asian languages (Cader, 2017; Speller, 2005). This stems from a stigma within East-Asian culture which unconsciously denies “the experience and expression of emotions and psychological symptoms” (Beiser; Speller, 2005). Over time, this has manifested into a limited lexical that can be translated into English to yield proper diagnosis. Both issues create communication barriers, while the first could be mitigated systematically, the latter proves to be more difficult due to its deeply rooted nature within the culture.

Mainstream Mental Health Facilities

As long as mainstream mental health facilities refuse to acknowledge nor accept cultural differences concerning mental health, it will lead to misdiagnosis and the installation of fear within the East-Asian community. In Asian traditions, describing somatic symptoms (migraines and insomnia) is less stigmatizing than mental symptoms (depression, anxiety, and addition) (Cader, 2017). Therefore, potential patients may seek help from physicians and family doctors to treat inherently mental issues. Take into consideration that in 2004, “70% of issues brought to family doctors are mental health issues,” however family doctors “are often not educated adequately to deal with such issues” (Cader, 2017). This will risk misdiagnosis in health centers as physicians will treat the patients according to their somatic symptoms. As a result, only physical concerns will be minimized rather than addressing their mental concerns (McLean Center, 2021). Patients may not see improvements within their mental health, and stop treatment early. In fact, it’s noted that Asians Americans were “more likely to terminate treatment prematurely in comparison to other ethnic groups” (Fairfax, 2017).

In addition, diagnosis within mainstream facilities often neglect the East-Asian culture values (Speller, 2005). Facilities rarely realize that an East-Asian patient may react differently than caucasian patients; therefore, they may suggest psychotherapyƒ and medication without understanding that these treatments may be highly stigmatized in East-Asian culture (Kramer 2002 et al.;Yang et al., 2019). Consequently, many East-Asian patients are scared away from treatment. This issue exists as a result of a gap in understanding within mainstream health care centers. The long-term effects of misdiagnosis and delayed treatment among the East-Asian community has both economic and cultural drawbacks.

Implications

Economic

As untreated mental health issues progress, patients may continue to seek help from the healthcare systems, ultimately becoming both an economic and ressources strain. In fact, the estimated cost for untreated mental health issues is an estimated $200 billion (Cader, 2017). Moreover, one in eight Emergency Department (ED) visits are concerning a mental health illness or substance (Kalter, 2019). In fact, there was a 75% increase in the number of ED visits due to mental health among youths aged 5-24 (Moroz et al., 2020). This calls for an increase of accessible and culturally-focused mental health services for Canada’s East-Asian citizens to decrease these visits. Especially for youths.

Cultural

By understanding East-Asian attitudes and needs concerning mental health, mainstream mental health care systems can develop culturally targeted treatments and campaigns that may be more effective for this minority. As this progresses, there may be more representation of East-Asians in the healthcare system as more patients begin to seek help.

This study

Effectiveness of Mental Health Campaigns

Mental health campaigns with the intent to educate have the potential to improve attitudes towards treatment (Gonzalez et al., 2019). During the evaluation of In One Voice campaign that raised awareness of youths towards mental health issues, participants noted that they were “significantly more likely to talk about and seek information related to mental health issues” post campaign; however, awareness only “grew more significantly among White respondents…than among respondents from other ethnic backgrounds” (Lingingston et al., 2014). This suggests that not all mental health campaigns promoting awareness based may be effective to all minorities despite their efficacy on the caucaisan demographic.

Effectiveness of a targeted demographic

Mental health campaigns are more effective when they are targeted towards an ethnicity. Consider the Chinese Mental Health Promotion program implemented by the Canadian Mental Health Association as an example. Their program includes “culturally rich and supportive activities” hosted by Canotonese and Mandarin staff, in addition to providing resources in Mandarin for seniors (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2016). As a result of acknowledging cultural differences in their approach to serving patients, 100% of participants felt “comfortable in asking for help” and 96% felt their “overall health has improved” (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2016). The implementation of a cultural specific campaign, in this case the targeted audience was Chinese, will yield higher results in improving the mental health of patients—this is due to the understanding of the culture. The program presents information and proposes treatment in a way that is not stigmatizing as well as providing staff that can speak their first language to mitigate language barriers. The results from non-culturally focused mental health campaigns compared to cultural-focused campaigns are drastic. As this case study was focused on seniors, this begs the necessity to implement similar treatment plans which targets youth East-Asians.

Addressing the Gap

According to our previous discussions, these newly immigrated youths from East-Asian will be the most vulnerable to mental health stressors. Considering this, they are also the ethnicity to least likely seek treatment. While there exists numerous resources for Asian Mental health, very rarely do these campaigns and support centres provide concrete data that track the effectiveness of their program nor are there enough Asian-focused mental health resources within a school setting. Cultural focused school-based interventions that are both “educational and experiential” will have the potential to “improve knowledge about mental health problems and decrease stigmatizing attitudes” (Essler et al., 2006). Until East-Asian culture is understood within a clinical setting, patients will remain ostracized to mainstream mental health facilities and resources. In this study, we will explore the potential of East-Asian focused mental health campaigns within a school setting, and provide quantifiable data supporting its efficacy.

Research Inquiry

To what extent will culturally-focused mental health campaigns increase the chances for newly immigrated East-Asian youths to seek mental health help?

Methodology

Design

By understanding the need for a culturally-focused approach of discussing mental health in order to alleviate stigma within East-Asian communities, this study will find the effectiveness of addressing cultural barriers of seeking mental health help for youths ages 15-17. This study is a needs assessment, for it was designed, and implemented, to address an identified gap within mental health campaigns that neglect cultural factors (O’Donnell, 2021). The results of this study will be determined based on the responses of a presentation that targets cultural discussion that was designed based on the needs of East-Asian youths that were not fully met from current mainstream mental health campaigns. To evaluate the effectiveness, quantitative data will need to be gathered with a survey based on the Mental Health Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS) before and after the presentation. These results are then compared. In addition, qualitative data from participants to better understand their cultural backgrounds and beliefs that may help better interpret the quantitative results.

Hypothesis

I hypothesize that the treatment will increase the student’s likelihood in seeking mental health treatment when they perceive they may need so; however, the change will not be drastic as cultural and individual attitudes are difficult to change in such a minimal amount of time.

Sampling Methods

In section East-Asian Immigrant Youths we have established that recently immigrated youths ages 15-17 from East-Asian communities are most vulnerable to mental health concerns, while simultaneously have the lowest percentage of seeking help. Therefore, this study collects primary data from two English Language Learning (ELL) Programs at Sentinel Secondary School in the Fraser Valley. The rationale behind conducting this study with these classes is that students are most likely to be international students and recently immigrated to Canada. In addition, it was confirmed that there were a majority of students from East-Asian countries. Please see the appendix for the questions. Classes included grades 10 to 11; thus, fitting within the age range of 15-17 that was previously identified as the target demographic of this study. Ultimately, these two classes were comparatively the most ideal in having students from the identified demographic in the Literature Review.

Presentation Content Selection and Method

The presentation was created with the objective to discuss seeking mental health help in consideration of cultural barriers. To ensure that the content is effective and addresses the basic knowledge of mental illness it includes information from existing campaigns such as The Elephant in the Room and UK initiative Mind. In addition to pre-existing campaigns, a professional counselor specializing in treating Asian families was consulted during the finalization process of the presentation. In consideration of the stigma surrounding the word “Mental Illness,” the presentation was based on addressing stress with the use of analogies and a prolonged anecdote to establish a more intimate relationship between the students and the information presented (Yang et al., 2019). To address language barriers, the presentation provided resources for seeking help in many Asian languages (Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Thai, Farsi, Arabic) as well as includes translations of the following words to better facilitate further discussion: Stigma, Mental Health, Treatment (Cader, 2017; Kramer et al., 2002). To address the possibility of misdiagnosis and lack of vocabulary for students to describe their symptoms, there was discussion on why one might choose to only describe physical symptoms and the implications (Beiser; Speller, 2005). A resource packet was given to better understand mental health that is available in multiple Asian languages. To address intimidation concerning mainstream mental health facilities, the presentation included different options of seeking help such as anonymous texting, talking to a school counselor, and even ecotherapy. These treatment methods are chosen specifically to show students that seeking help isn’t as stigmatizing as mainstream mental health facilities may portray it to be (Speller, 2005).

Instruments of Data Collection

Survey

The primary instrument of data collection is a survey that assesses both qualitative and quantitative data. This survey will be referred to two parts of Part A and Part B within this study, however for the participants it will be presented within sections of the information that is being collected. Part A refers to the qualitative collection of data. This includes: nationality; English proficiency; number of years in Canada. Their perceived level of English proficiency will be noted using the Common European Framework of References for Languages (CEFR) (Jones). Part B refers to the quantitative collection of data. This includes the Mental Help Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS), which is a 9-item instrument designed to measure the respondent’s attitudes towards seeking mental health help from a professional if they identify themselves to be in the need of a mental illness or concern. This scale was developed by Dr. Joseph H. Hammer, Dr. Michael C. Parent, and Douglas A. Spiker. The reliability and validity for the MHSAS score is peer-reviewed, and published in the Journal of Counseling Psychology. The factor structure of the MHSAS is similar to a unidimensional measurement model which means that most of the 9 questions hold the goal of evaluating “help seeking attitudes” (Hammer, 2018). For the sake of mitigating language barriers, students will not be asked to complete the entire MHSAS, rather only those that are perceived to be easily understood. The questions were chosen based on Macmillan Dictionary’s Red Words and Stars feature that categorized words to be frequently, more frequently, or most frequently used (Macmillan Dictionary, 2021). Questions that included words which received three stars–meaning most frequently used–were used. The questions will be available in the appendix for further consultation.

Procedures

To begin, a survey will be distributed to all students within Sentinel Secondary’s English 10 and Academic Writing 11 class (n=36). As mentioned above, the questionnaire will contain two parts: Part A to identify their ethnicity, language proficiencies, number of years in Canada, and Part B to report their attitudes towards seeking mental health help with the Mental Help Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS). View the previous section (“Survey”) for a detailed overview of the survey’s contents. After the completion of the survey, the presentation will follow. See section Presentation Content Selection and Methods for rationale and presentation contents. Two weeks following the presentation, the same cohort will be asked to fill out the survey once more. This procedure will be repeated for each class. Attitudes from before the presentation will be compared to attitudes after the presentation to establish its efficacy, and to determine if there is a need for an East-Asian focused mental health awareness and education in school settings.

Delimitations

A possible delimitation is that the short time interval of the treatment will not be enough to substantially shift mental health attitudes since these attitudes are governed by pre-existing beliefs that are based on religion, culture, and family. However, in a Cochrane review of mass media intervention for smoking “found no significant association between campaign duration and effectiveness” and “other related research has shown that serial mass-media campaigns may risk becoming redundant” (Evans-Lacko et. al., 2010). Therefore, suggesting the plausibility of my short-term study. Moreover, despite there being no correlation between duration and effectiveness, there exists the question: Will the short-term treatment be enough to yield observable results that can be used for analysis and evaluation? In a case study where the mental health campaign (Time to Change) was promoted in Cambridge for 4-weeks in comparison to 3-years claimed that there exists shifts in anti-stigma mental health attitudes despite short time intervals:

There was a 24% (pre = 58%, post = 82% p < 0.001) increase in persons agreeing slightly or strongly with the statement: If a friend had a mental health problem, I know what advice to give them to get professional help, following the campaign. Additionally, for the statement: Medication can be an effective treatment for people with mental health problems, there was a 10% rise (pre = 74%, post = 84% p = 0.05) in the proportion of interviewees responding ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ following the campaign. (Evans-Lacko et al. 2010)

Considering how this month-long campaign may yield observable results, it can be inferred that my two-week campaign, where I will employ post-treatment check-ins and an increased personal approach of presentation and conversation with the students, may yield observable results.

Furthermore, there could also exist a challenge in language barriers in the surveys and the treatments as the sampled demographic are assumed to not have a high level of English proficiency. This will be mitigated by including translation during the presentation, as well as using the MHSAS as the nature of its completion only requires singular, and simple, vocabularry. The section Survey provides the criteria of which questions from the MHSAS were selected.

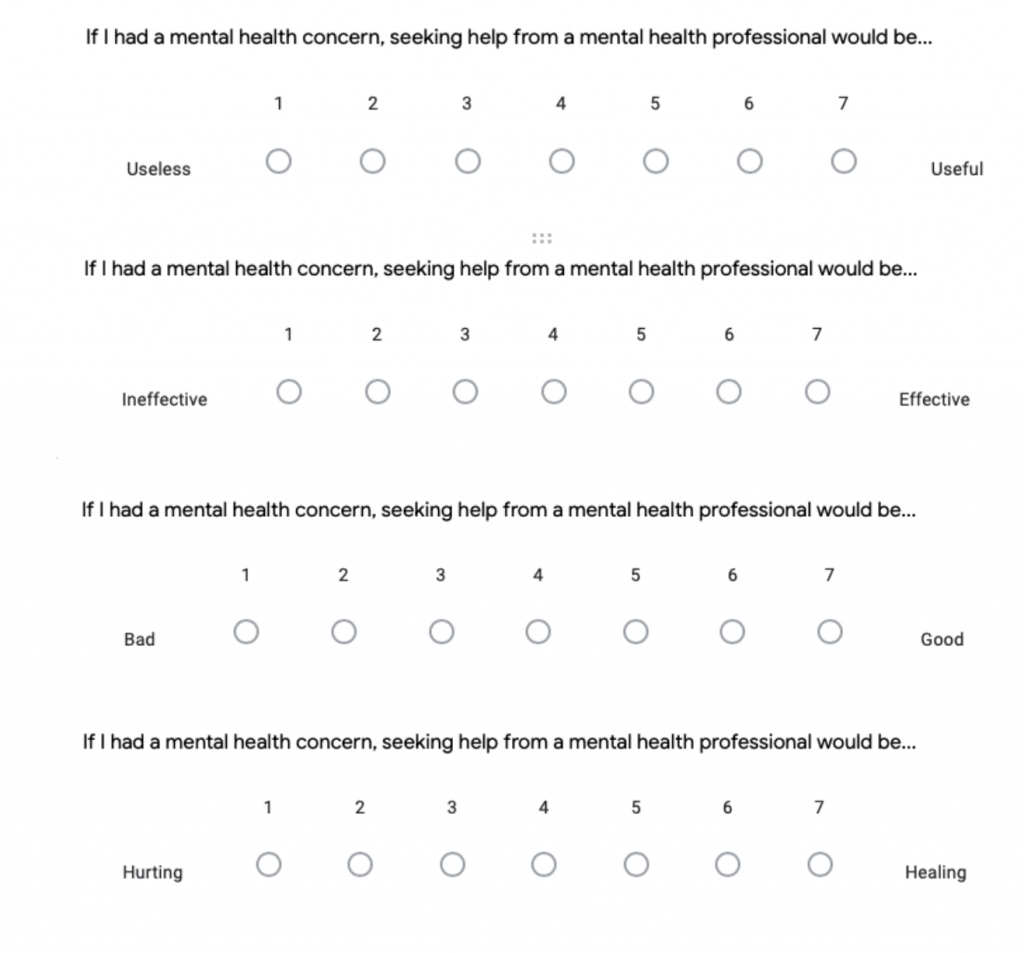

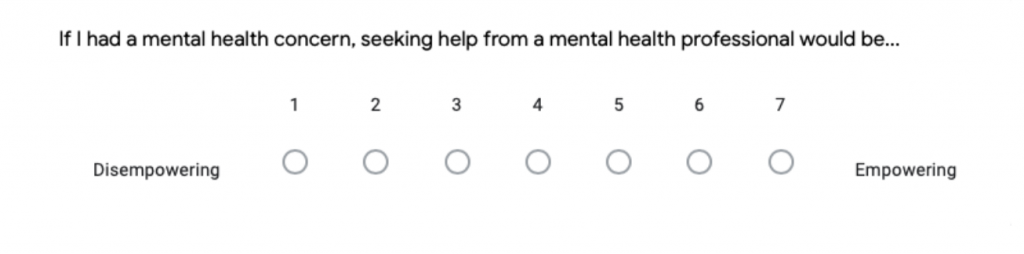

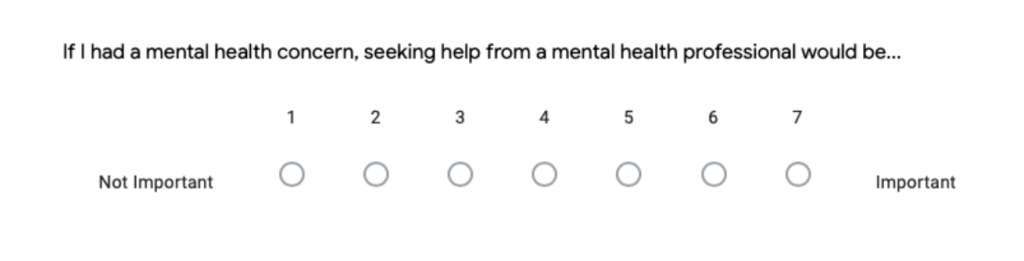

Data Analysis

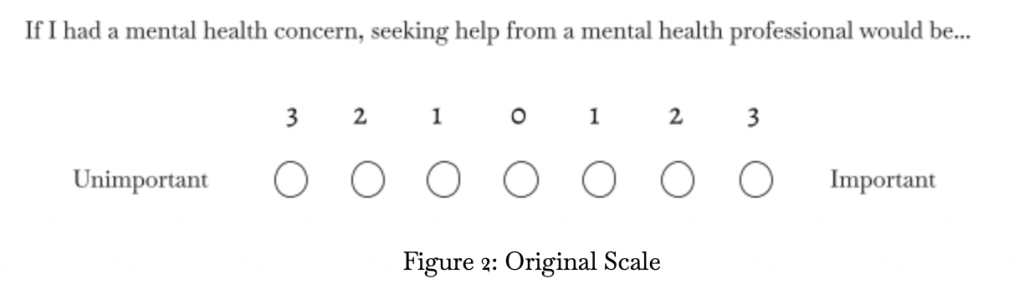

The MHSAS uses a “seven-point semantic differential scale” and contains nine statements for the participants to answer to yield an average score. This average score of pre-treatment and post-treatment will be compared with the goal to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment. In this study, this scale is modified. Before modification, the scale labels were: 3,2,1,0,1,2,3.

The following image is an example of the original scale.

Figure 2: Original Scale

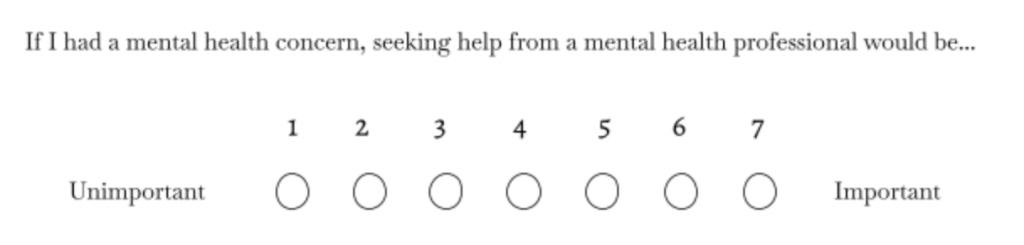

In the survey, the points were converted with reverse coding to facilitate finding the average of the answers in the analysis part of this study. In reverse code, the scale values where the score of “1” will be indicated to the circle to the furthest left and “7” to the furthest right. The reverse code is what was presented to the participants. With “4” being neutral.

The following image is an example of what the participants see during the survey after reverse coding.

Figure 3: Modified Scale

To find the average, the scores are added then divide it by the total number of answers. For example, if a participant had only answered 8 questions, you will divide the sum of their scores by 8 rather than 9. This gives the participants the possibility to skip questions if they are unclear which will yield more accurate results. Following, the mean scores are compared. First, the answers of each question are compared. Second, the overall average of each participant will be analyzed. Overall, a higher score means more positive attitudes.

The qualitative analysis will be presented graphically, and considered during the discussion on the significance of our quantitative results.

Results

Survey

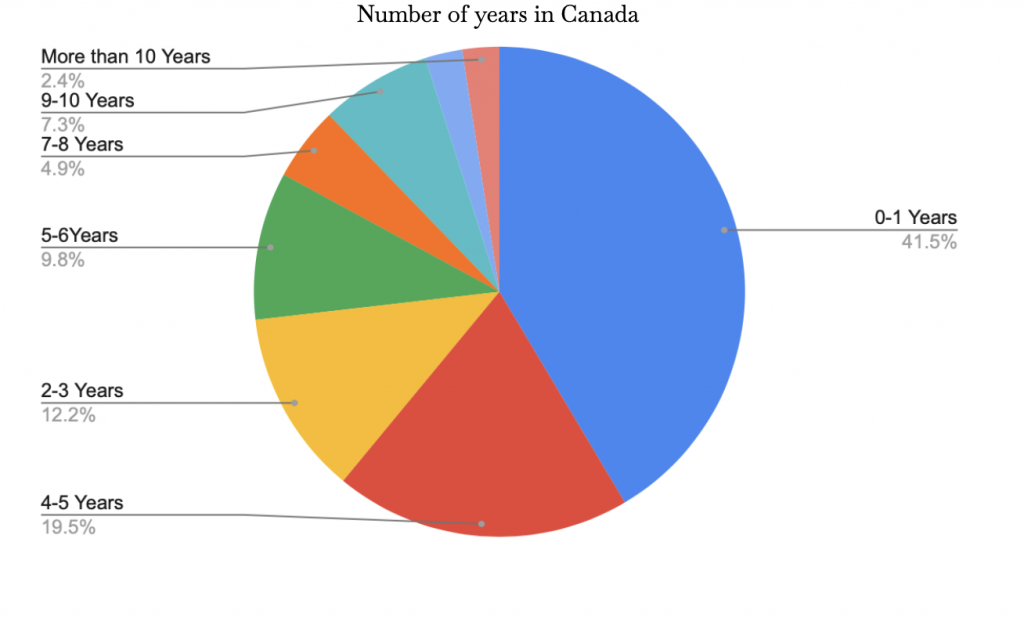

The survey yielded results from 41 students in Sentinel Secondary. As stated in the methodology, these respondents were chosen based on their shared characteristics with our targeted demographic as identified in the literature review: Newly immigrated East-Asian Youths. The group of respondents of this study came from a range of different ethnicities in Asia. Nevertheless, more than 60% of the respondents were from East-Asian countries. The following tables will be presenting data from East-Asian respondents only unless mentioned. Figure 4 and 6 is to highlight our demographic. English Proficiency Levels definitions can be referenced to in the appendix. Figure 4 and 6 provides an overview of the demographic with respect to the student’s number of years in Canada as well as their English proficiency levels. Graphic 6 and 7 compares attitudes of respondents concerning mental health and mental health treatment before and after the video treatment.

Demographic

Figure 4: Number of years in Canada

Figure 5: English Language Proficiency Levels

Attitudes

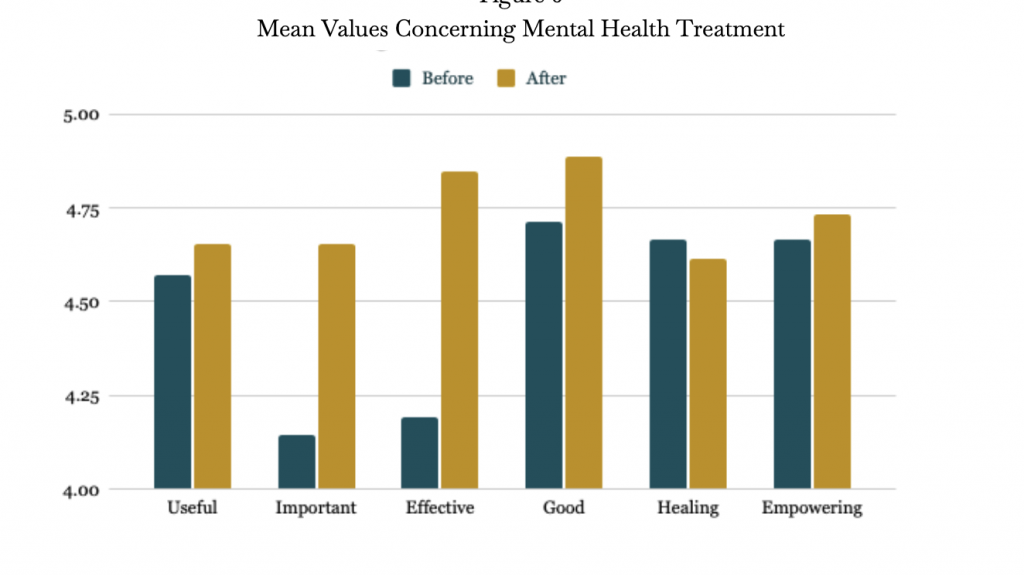

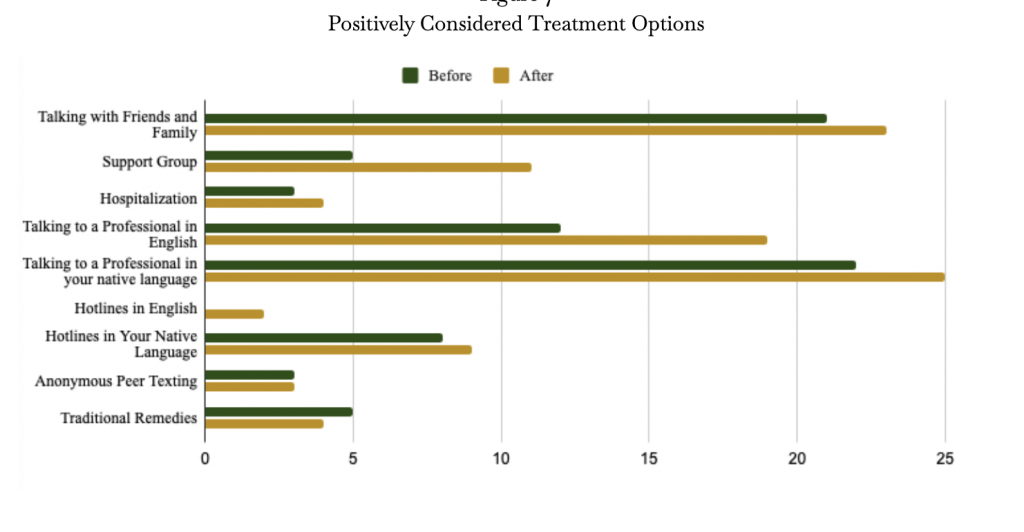

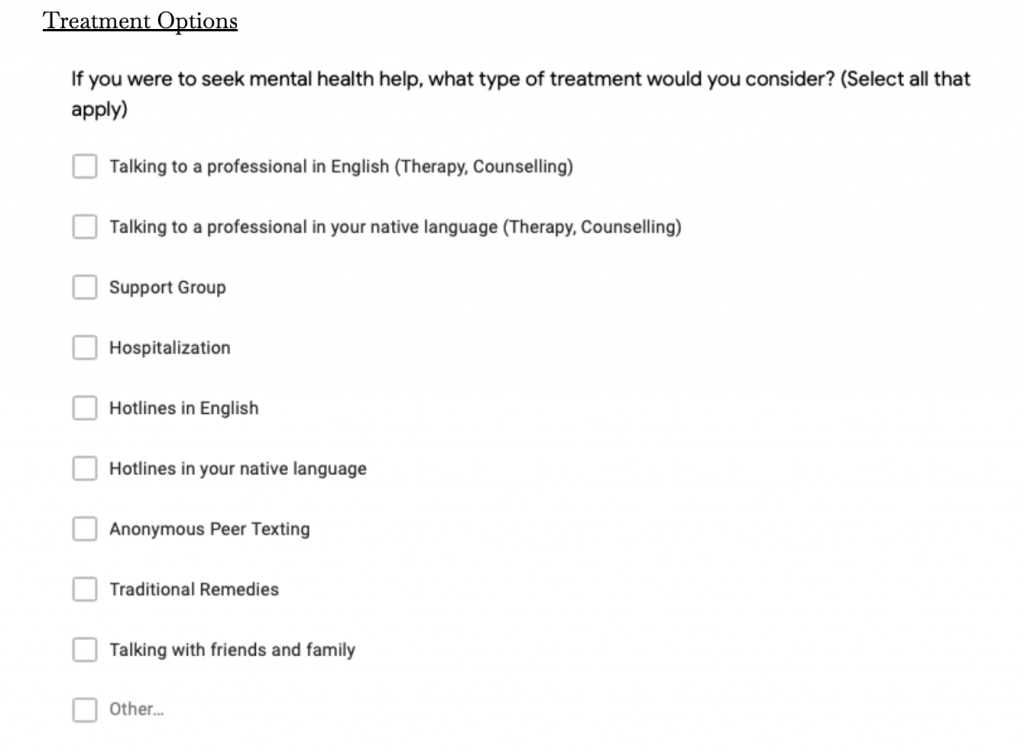

The following tables represent the pre and post treatment attitudes towards receiving mental health help. Figure 6 compared how the students perceived receiving mental health help before and after the video treatment. Positive attitudes are characterized by higher values. Figure 7 depicts the number of respondents that believe the listed treatment options are beneficial, and are open to in the event that they experience a mental health concern. This data represents that of the East-Asian respondents only.

Figure 6: Mean Values Concerning Mental Health Treatment

Figure 7: Positively Considered Treatment Options

Discussion

Significance of Results

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of a mental health campaign that focused on cultural differences between Western and Asian communities. Respondents reported a change in mean scores for their positive attitudes before and after the treatment. In addition, respondents were more open to different treatment methods as well. These results corroborate the hypothesis that a cultural-focused mental health campaign will increase the likelihood of a youth to seek mental health help if they perceive they may need to.

When asked to describe their attitudes towards seeking mental health help, there was an increase in positive attitudes after the treatment. In a score out of seven—with seven being the most positive—the average mean score for East-Asians when ranking if mental health help was important increased by 12.3%. When asked to rate the effectiveness of mental health treatment, positive attitudes increased 15.7%. According to a study from the journal of Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, positive “beliefs about the effectiveness of mental health treatment were associated with use of mental health services” (Ten Have et al., 2009). This suggests that the treatment has had the ability to increase the likelihood for East-Asian youths to seek mental health help through increasing positive attitudes towards the subject.

Moreover, respondents also increase their positive attitudes towards different treatment options. For example, after the treatment respondents were 12% more likely to talk to a professional in English, 12.5% more likely to go to support groups and 5% more likely to call a mental health hotline in English. Additionally, there was an increase in the fact that respondents were willing to talk to their family and friends about their mental health concerns. When students are equipped with the right knowledge about the different types of mental health help that are not limited to treatments confined to the conventional western medical system, they will be more likely to seek this help directly rather than risk misdiagnosis by going to a physician to address their somatic symptoms (Cader, 2017: McLean Center, 2021).

Nevertheless, there is a discrepancy between seeking mental health help in a respondent’s native language in contrast to English. On average, respondents were 20% more willing to seek help in their native language. Therefore, in correlation with the US National Library of Medicine, language remains a core cultural barrier that is impeding East-Asians from mental health care (Bauer et al., 2010).

Significance of Study

In contrast to previous studies on this similar subject, this study provided insights on two regions: the effectiveness of a culturally-focused mental health campaign, and the responsiveness of having the campaign set in a school-based setting when communicated by a peer rather than an authority. As previously mentioned, the In One Voice campaign, there was a discrepancy in responsiveness between white and non-white respondents. As a general trend, non-white respondents reported they were less likely to seek help than their white peers after the campaign where the average change in positive attitudes changed from 6% to 15.6% (Fairfax, 2017). Non-white respondents averaged a lower change in attitudes. Of course, comparing the results of this study and the In One Voice campaigns would be difficult due to the difference in the scale of the campaigns, the resources involved, and its duration; however, there is high potential for this culturally-focused method of discussing mental health to exceed in effectiveness than previous non-culturally focused campaigns based on the results of this study.

Responsiveness of the treatment in this campaign could be due to the following characteristics employed in the delivery of the presentation: story formatting; language resources before, after and during the presentation; non-hospitalization treatment options; peer presentation. To begin, the University of Utah claims that using an analogy and using stories is an effective way to communicate serious illness in a way that brings the speaker and the audience closer, and even more susceptible to the information presented (University of Utah, 2017). Considering this, the use of a fictional personage called Taylor—a gender neutral representation of a newly immigrated East-Asian youth—in this study’s treatment to communicate the detriments of untreated mental illness and recognizing its symptoms enhances the message promoted.

Moreover, this study also addressed language barriers by having translations of mental health related words as well as having a presenter who spoke English, French and Mandarin. The presenter interacted with most of the mandarin speaking participants in regards to translation of survey details before and after the treatment. This interaction could increase understanding of the information and survey for the individuals; thus, lead to decreasing language barriers. Nevertheless, it may not be enough to change attitudes towards mental health, nor increase the number of youths willing to seek help, for it only helps them understand the content (Pew Research Center, 2017; Xia, 2021). Lastly, the use of a peer presenter may have also increased positive attitudes to the materials presented. A study conducted in a Hong Kong University concluded similarly claiming that “‘peer-level’ patient interactions significantly decrease prejudicial attitudes, while clinician-to-patient interactions do not” (Adhorsu, 2021).

Limitations

Despite seeing promising figures of overall improving positive sentiments towards seeking mental health help, this study faced limitations that could have restricted the observability and accuracy of these results. This study makes the assumption that the students will take action in the levels they have indicated towards treating their mental concerns if they perceive to have one. However, the accuracy of these results is hindered for there is no ressources to track the respondents after the treatment to track their decisions. This will require a longer duration of the study, and an increased scale of personnel to keep updated records of the respondents post treatment.

Conclusion and Future Research

This needs assessment has successfully identified the need for a culturally-focused campaign to be implemented in schools for newly immigrated East-Asian youths. Future research should implement a longer campaign duration and increased ressources. Such resources may include professional translators to create fully translated presentations, and continuous tracking of the respondents post-treatment within a 2 year period (Fairfax, 2017). Nevertheless, considering the effectiveness of a short treatment within this study, it should be considered that similar needs assessments be conducted for other Asian communities. The implementation of a continuous culturally-focused campaign can lead to decreased spending within the Canadian government as misdiagnosis decreased, and aid to break the cycle of mental health stigma within the East-Asiam community.

Work Cited

Ahorsu, Daniel Kwasi, et al. “Effect of a Peer-Led Intervention Combining Mental Health Promotion with Coping-Strategy-Based Workshops on Mental Health Awareness, Help-Seeking Behavior, and Wellbeing among University Students in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Mental Health Systems, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33422098/.

Bauer, Amy M., et al. “English Language Proficiency and Mental Health Service Use among Latino and Asian Americans with Mental Disorders.” Medical Care, vol. 48, no. 12, 2010, pp. 1097–1104., https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181f80749.

Cader, Nurul Hinaya. Exploring Experiences of Mental Health in Second Generation South Asian Canadians. University of Ontario Institute of Technology, PhD Thesis. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK44249/ Accessed 25 Oct. 2021.

“Chinese Mental Health Promotion .” Fraser, 31 May 2016, https://vancouver-fraser.cmha.bc.ca/programs-services/chinese-mental-health-promotion/.

Chong, Siow Ann, et al. “Perception of the Public towards the Mentally Ill in Developed Asian Countries.” Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, vol. 42, no. 9, Sept. 2007, pp. 734–739. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0213-0.

“English Proficiency of Chinese Americans.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 8 Sept. 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/chart/english-proficiency-of-chinese-population-in-the-u-s/.

Essler, Vicky, et al. “Using a School-Based Intervention to Challenge Stigmatizing Attitudes and Promote Mental Health in Teenagers.” Journal of Mental Health, vol. 15, no. 2, 2006, pp. 243–250., https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230600608669.

Evans-Lacko, Sara, et al. “Evaluation of a Brief Anti-Stigma Campaign in Cambridge: Do Short-Term Campaigns Work?” BMC Public Health, vol. 10, no. 1, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-339.

Fairfax, Colita Nichols. Social Work, Marriage, and Ethnicity: Policy and Practice. Routledge, 2017.

González-Sanguino, C., Potts, L.C., Milenova, M. et al. Time to Change’s social marketing campaign for a new target population: results from 2017 to 2019. BMC Psychiatry 19, 417 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2415-x

Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. “Asian Heritage Month… by the Numbers.” Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, 6 May 2021, https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/dai/smr08/2021/smr08_250.

“Health Care Insider: How Analogy Can Help Physicians Communicate Effectively.” University of Utah Health, https://healthcare.utah.edu/the-scope/shows.php?shows=0_ld7ka9ir.

Kalter, Lindsay. “Treating Mental Illness in the ED.” AAMC, 3 Sept. 2019, https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/treating-mental-illness-ed.

Kramer, Elizabeth J et al. “Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans.” The Western journal of medicine vol. 176,4 (2002): 227-31.

Livingston, James D., et al. “Another Time Point, a Different Story: One Year Effects of a Social Media Intervention on the Attitudes of Young People towards Mental Health Issues.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, vol. 49, no. 6, 2014, pp. 985–990., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0815-7.

“Macmillan English Dictionary.” Common English Words – Macmillan Dictionary, 2021, https://www.macmillandictionary.com/learn/red-words.html.

“Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General.” =, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1037/e647822010-001.

“Mental Help Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS).” Dr Joseph H Hammer, http://drjosephhammer.com/research/mental-help-seeking-attitudes-scale-mhsas/.

Moroz, Nicholas, et al. “Mental Health Services in Canada: Barriers and Cost-Effective Solutions to Increase Access.” Healthcare Management Forum, vol. 33, no. 6, 2020, pp. 282–287., https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470420933911.

O’Donnell, Emily. “Seven Steps for Conducting a Successful Needs Assessment.” NICHQ, 12 Jan. 2021, https://www.nichq.org/insight/seven-steps-conducting-successful-needs-assessment.

Speller, Heather K. “Asian Americans and Mental Health: Cultural Barriers to Effective Treatment.” Elements, vol. 1, no. 1, 2005, https://doi.org/10.6017/eurj.v1i1.8880.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Racial/ Ethnic Differences in Mental Health Service Use among Adults. HHS Publication No. SMA-15-4906. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015.

Ten Have, M., et al. “Are Attitudes towards Mental Health Help-Seeking Associated with Service Use? Results from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, vol. 45, no. 2, 2009, pp. 153–163., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0050-4.

“The People of Singapore.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Singapore/The-people.

“Why Asian Americans Don’t Seek Help for Mental Illness.” Why Asian Americans Don’t Seek Help for Mental Illness | McLean Hospital, 10 May 2021, https://www.mcleanhospital.org/essential/why-asian-americans-dont-seek-help-mental-illness.

Xia, Lucy. “Asian Youths Face Significant Mental Health Challenges, Report Finds.” Stuff, 28 June 2021,https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/125587674/asian-youths-face-significant-mental-health-challenges-report-finds.

Yang, Fang, et al. “Stigma towards Depression in a Community-Based Sample in China.” Comprehensive Psychiatry, W.B. Saunders, 6 Dec. 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010440X19300756.

Appendix

Survey

Consent Form:

Participation in this study is voluntary. If you agree to participate in this study, please continue in filling out the following google form. All answers will remain anonymous.

Participating in this study may not benefit you directly, but it will help us learn about East-Asian attitudes towards mental health treatment. If you may find answering some of the questions upsetting, you may skip any questions you don’t want to answer.

This study is being conducted by Catherine Xiong as a part of the AP Research course taken at Sentinel Secondary.

If you have any questions about this study, please contact Catherine Xiong at [email protected].

By completing this survey, you are consenting to participate in this study.

Languages:

Please read the descriptions below and indicate your perceived level of English proficiency. If you are unsure, please select the one that best describes you. If you already know your level from previous assessments, please confirm your selection by reading the description of the level in this survey.

There will be three choices. For example, A1 and A2 will be categorized as only A. If you are either, please select the letter.

The “A” Level

Beginner and elementary language learners can understand and communicate basic expressions used for shopping, family, and employment. They can interact simply with others with routine interactions. However, describing medical symptoms and understanding diagnosis is challenging.

The “B” Level

Intermediate and upper intermediate language learners can understand the main ideas of technical texts used in school. They can interact spontaneously with native speakers with less effort. They can describe their symptoms and understand diagnosis in simple terms.

The “C” Level

Advanced and proficient language learners can understand almost everything in texts and during conversations. They can express their ideas, as well as speak all in academic, social and professional settings. They have no trouble describing their symptoms and understanding diagnosis.

Mental Health Attitudes (MHSAS)

Definition: “Mental Health Treatment”

Seeking help from an external source. For example, seeing a professional, calling hotlines, group sessions, texting a professional, therapy.

Click Here to access the presentation slides.