Megan Wang, Year 2 Research

Abstract

Although the skin microbiome is similar amongst individuals, certain factors, such as the type of skincare applied, can alter its composition. This study aims to understand how common skincare ingredients, such as Vitamin C, retinol, and resveratrol affect yeast growth, a common fungus located on the skin. Through the experiment, it is observed that yeast colony growth increased after skincare product application; however, the rate of growth is minimal. Despite the limited data collected due to the short time span of the study, the results suggest that ingredients used in skincare products do positively affect the growth of skin microflora, but usually not to an extent that skincare disorders could develop.

Introduction

The skin is the body’s largest organ, which hosts a multitude of microorganisms living symbiotically with one another. Such organisms include viruses, bacteria, fungi, and mites, which function together as a mini ecosystem (Grice et al., 2011). Yeast, in particular, is shown to boost the growth of other beneficial bacteria for the microbiome, as shown in a study by Li et al. (2021) with a topical lotion with yeast extract. Thus, the altering of yeast concentrations on the skin could affect the growth of other microorganisms to act as a skin barrier.

Although skin microbiota are fairly similar amongst people, certain factors can alter its composition. There are two categories of factors that contribute to this: host factors, such as age, location, and sex, and environmental factors, such as one’s occupation, clothing choice, antibiotic usage, and cosmetics (Grice et al., 2011). Additionally, according to studies by Pinto et al. (2021), certain preservatives, such as parabens, and specific products can alter the skin’s microbiome and lipid covering. Such products include moisturizers, soaps, and anti-aging oily products.

The role of skin microflora is to protect the skin from pathogens, however, if its composition is affected by ingredients in skincare products, it weakens the skin’s protective barrier and in severe cases, could lead to skin disorders such as premature ageing, dehydration, and acne (Holland and Bojar, 2002). Vitamin C, retinol, and resveratrol are common ingredients in skincare products that can help with brightening, acne, and anti-ageing respectively. For example, in a study conducted by Lam et al. (2021), a variety of treatments, including retinoids (a Vitamin A derivative that is similar to retinol), were tested to determine its effectiveness on patients’ acne. Isotretinoin was found to increase diversity in bacteria on the skin, while topical trentinoin was found to decrease diversity. However, both treatments resulted in a sharp decrease in levels of Cutibacteria, a key contributor to acne.

Materials and Methods

Before growing the yeast colonies, YEPD agar needed to be prepared in advance, which was completed following the instructions. The broth media was autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes before being poured equally into sterile petri dishes. To prepare the yeast for growth, a 5-gram packet of Lalvin EC-1118 All-Purpose wine yeast was combined with 50 mL of water into an erlenmeyer flask. The mixture was heated with a hotplate until it reached 37°C. After the mixture was slightly cooled, 500 μL of the yeast mixture was pipetted into three petri dishes each. Three petri dishes of yeast colonies were grown and incubated to confirm that culture growth was successful. The week after, 4 small plastic tubes had distilled water pipetted into them: 1000 μL of water in one tube, and 900 μL of water in the other three tubes. A swab of the original yeast culture was inserted into the tube with 1000 μL of water and mixed thoroughly. 100 μL of the solution was pipetted into the second tube and combined as well. This process repeats with the other two tubes until all plastic tubes have a solution of yeast culture and water of various concentrations. The tube with the highest concentration of yeast was labelled “Dilution 1”, and the tube with the lowest concentration named “Dilution 4”. For each dilution, 100 μL of the solution was added to each of the 4 petri dishes; the total number of petri dishes used should be 16 (excluding the 3 petri dishes of original yeast cultures). Once the solutions were pipetted onto the sterile agar, they were spread throughout the petri dish evenly and incubated for a week.

After a week of growth, resveratrol, retinol, and Vitamin C serums were added to the new yeast colonies. In three separate plastic tubes, four drops of each serum are combined with 2000 μL of water and mixed thoroughly, to ensure they are not overly viscous. Each serum will be pipetted onto 4 petri dishes, one for each dilution. 500 μLof the serum solution are carefully pipetted into each petri dish, being careful not to disturb the original colony growth. The four petri dishes used for the control will have 500 μL of distilled water pipetted into them instead. Once all of the petri dishes had been prepared, they were incubated for another week. Pictures of the yeast colonies were taken before and after the skincare product application. Additionally, in order to measure the growth of yeast colonies, the radius of the colonies were measured with a ruler before and after skincare product application, and the results were compiled into a spreadsheet and graph.

Results

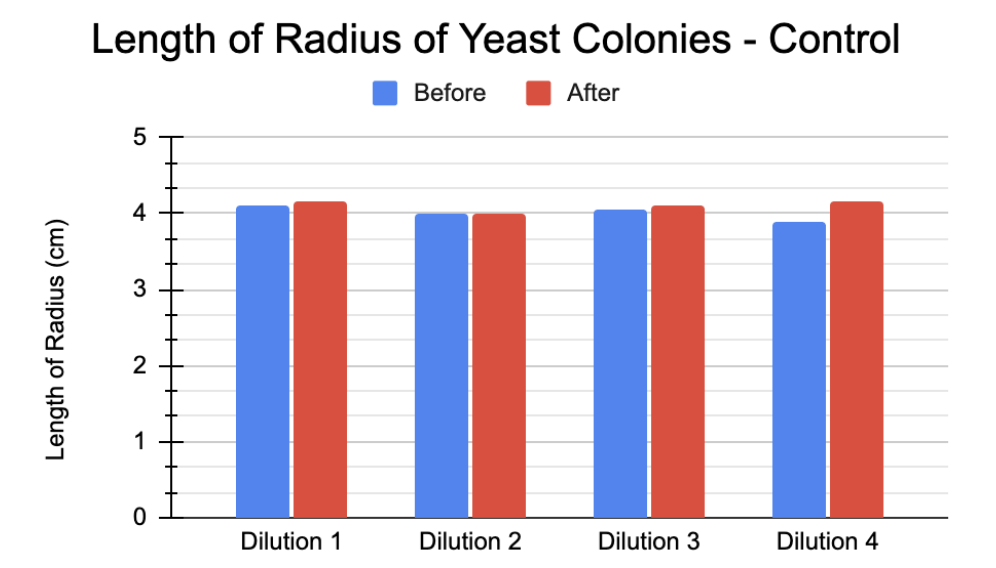

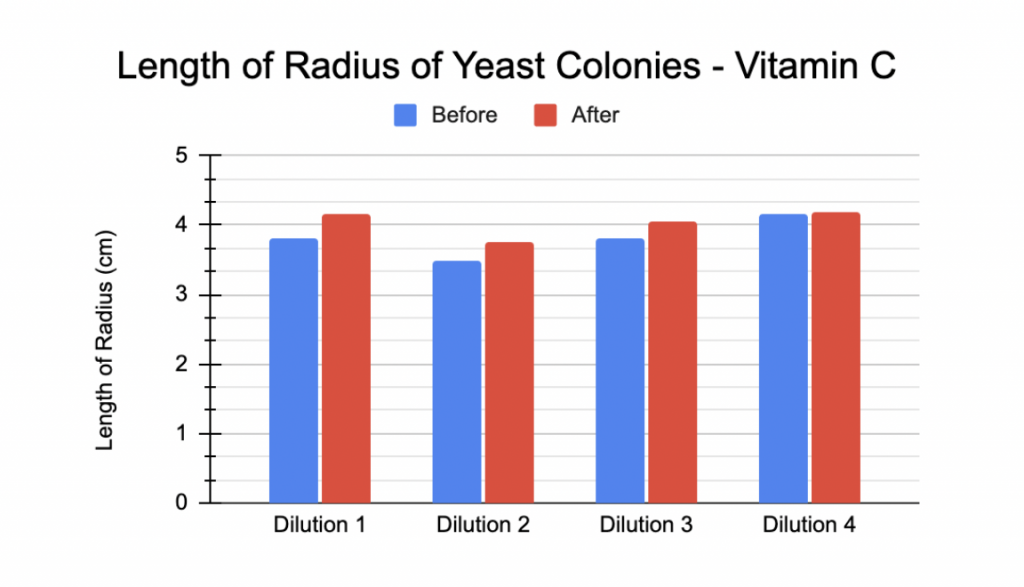

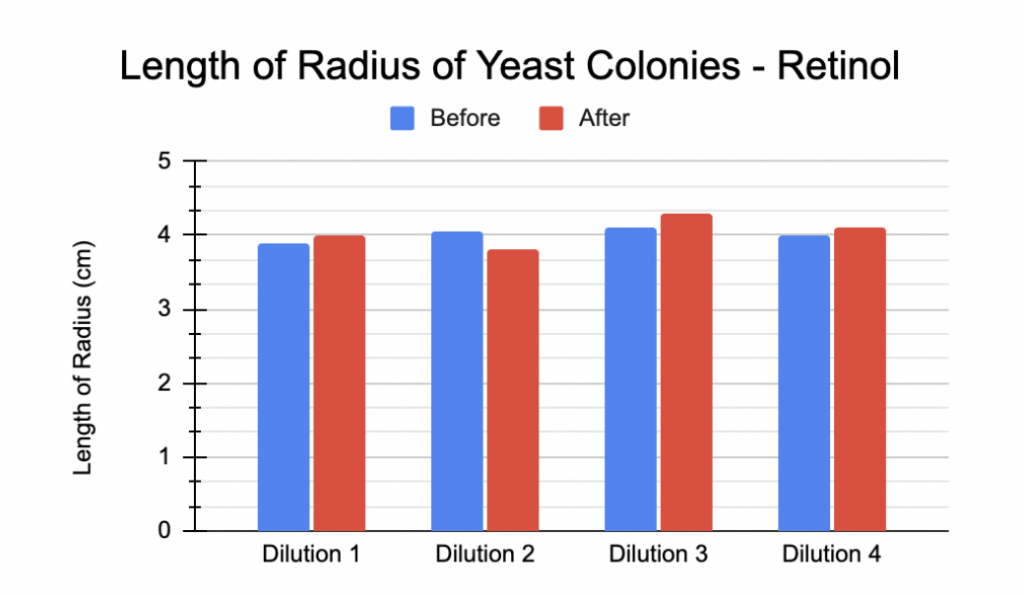

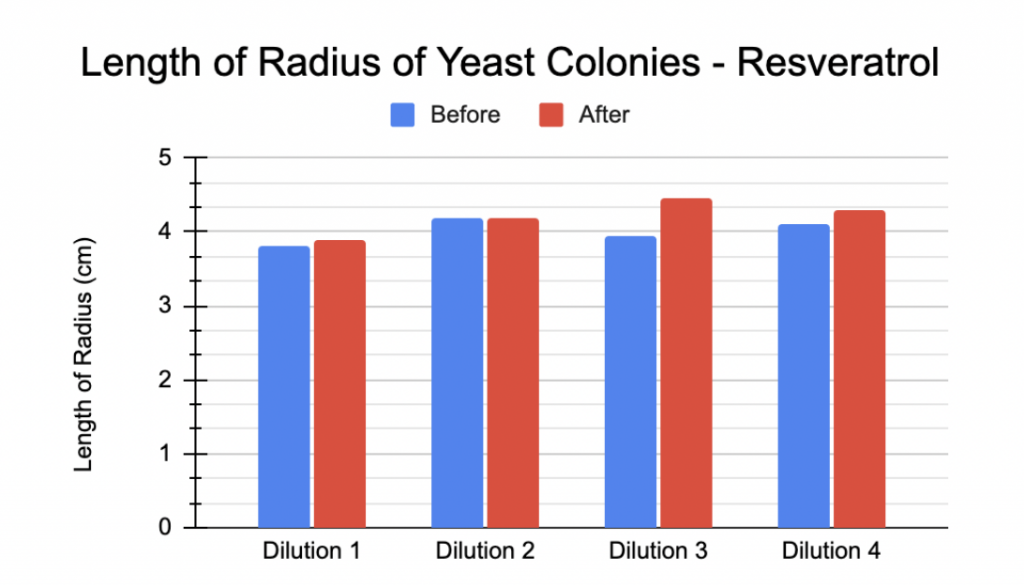

In general, after application of skincare products, the length of the radius increased, with the resveratrol trial group having the largest positive change in growth. By contrast, the length of the radius for the control petri dishes did not alter drastically. The following graphs show all four trial groups—control, Vitamin C, retinol, and resveratrol—and their respective changes in growth measured by the length of the colonies’ radii. Please see figures 1a to 1d.

Figure 1a: Radius of Control Yeast Colonies before and after product applications

Figure 1b: Radius of Vitamin C Yeast Colonies before and after product

applications

Figure 1c: Radius of Retinol Yeast Colonies before and after product applications

Figure 1d: Radius of Resveratrol Yeast Colonies before and after product

applications

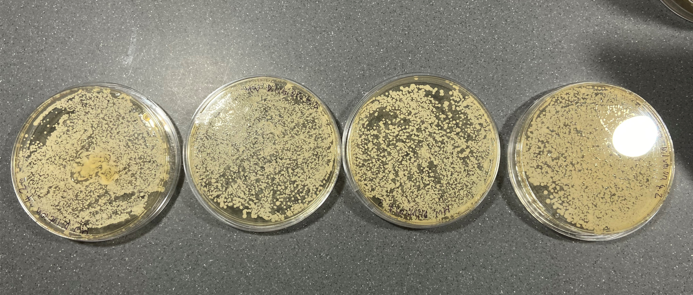

In addition, pictures of the yeast colonies before and after skincare product application were taken as well to serve as a record of the yeast colonies’ qualitative changes. Below is a sample set-up for the control yeast colonies. Please note that all petri dishes are placed in order, from Dilution 1 to the far left to Dilution 4 on the far right. It isobserved that after product application, while the length of the colonies’ radii have not drastically changed, the colonies themselves are denser in the second image; see figures 2a and 2b.

Figure 2a: Control yeast colonies before product application

Figure 2b: Control yeast colonies after product application

Discussion

After skincare products were applied to the yeast colonies, the colonies’ growth was only marginally increased. This could be due to low concentration of the skincare products applied (since they were diluted), and the growth could be attributed to the yeast’s natural growth cycle over a week. These results demonstrate that when one uses skincare products at their full concentration, the ingredients in their products could alter their natural skin microbiome; however, unless it is in an abnormally high concentration, it will usually not be affected to an extent where the user develops skin disorders.

There are also some minor issues in this study that need to be addressed. At first, the serums were difficult to apply to the colonies, as the former were too viscous to spread on directly, and would have altered the appearance of the already established colonies. Additionally, it was impossible to count all of the yeast colonies on each petri dish, as they were too small. Both of these issues could be resolved by using a spectrometer, which would allow one to count the precise number of yeast cells in a liquid culture, and combine it with liquid serums without any alteration to the culture’s appearance. To further the direction of this study, I would consider testing different skincare ingredients on yeast colonies and observe the yeast growth for a more prolonged period of time to understand the long-term effects of this experiment. Additionally, building on previous research, I would examine how the growth of yeast affects the population of other microorganisms to understand the former’s role in maintaining diversity within the skin microbiome.

References

Grice, Elizabeth A., and Julia A. Segre. “The Skin Microbiome.” Nature Reviews Microbiology, vol. 9, no. 4, 2011, pp. 244–253., https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2537.

Holland, Keith T., and Richard A. Bojar. “Cosmetics.” American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, vol. 3, no. 7, 2002, pp. 445–449.,

https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200203070-00001.

Huffnagle, Gary B., and Mairi C. Noverr. “The Emerging World of the Fungal

Microbiome.” Trends in Microbiology, vol. 21, no. 7, 2013, pp. 334–341.,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2013.04.002.

Lam, Megan, et al. “The Impact of Acne Treatment on Skin Bacterial Microbiota: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, vol. 26, no. 1, 2021, pp. 93–97., https://doi.org/10.1177/12034754211037994.

Li, Cecilia, et al. “28140 How a Lotion with Prebiotic Yeast Extract Regulates the Environmental Aggressors Impact on the Skin Microbiome.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 85, no. 3, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.715.

Pinto, Daniela, et al. “Effect of Commonly Used Cosmetic Preservatives on Skin Resident Microflora Dynamics.” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88072-3.

Pullar, Juliet, et al. “The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 8, 2017, p. 866., https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080866.

Taylor, Emma J., et al. “Resveratrol Demonstrates Antimicrobial Effects against Propionibacterium Acnes in Vitro.” Dermatology and Therapy, vol. 4, no. 2, 2014, pp. 249–257., https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-014-0063-0.References

Grice, Elizabeth A., and Julia A. Segre. “The Skin Microbiome.” Nature Reviews Microbiology, vol. 9, no. 4, 2011, pp. 244–253., https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2537.

Holland, Keith T., and Richard A. Bojar. “Cosmetics.” American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, vol. 3, no. 7, 2002, pp. 445–449.,

https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200203070-00001.

Huffnagle, Gary B., and Mairi C. Noverr. “The Emerging World of the Fungal

Microbiome.” Trends in Microbiology, vol. 21, no. 7, 2013, pp. 334–341.,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2013.04.002.

Lam, Megan, et al. “The Impact of Acne Treatment on Skin Bacterial Microbiota: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, vol. 26, no. 1, 2021, pp. 93–97., https://doi.org/10.1177/12034754211037994.

Li, Cecilia, et al. “28140 How a Lotion with Prebiotic Yeast Extract Regulates the Environmental Aggressors Impact on the Skin Microbiome.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 85, no. 3, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.715.

Pinto, Daniela, et al. “Effect of Commonly Used Cosmetic Preservatives on Skin Resident Microflora Dynamics.” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88072-3.

Pullar, Juliet, et al. “The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 8, 2017, p. 866., https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080866.

Taylor, Emma J., et al. “Resveratrol Demonstrates Antimicrobial Effects against Propionibacterium Acnes in Vitro.” Dermatology and Therapy, vol. 4, no. 2, 2014, pp.